Part 1 appears here, Part 2 appears here, Part 3 appears here, Part 4 appears here.

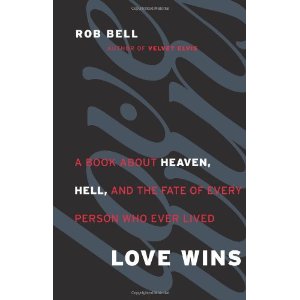

Chapter 4: Does God Get What God Wants?

In this chapter the central dogma becomes especially evident. It’s the old conundrum: God is either sovereign or loving. Bell bases his conclusion on the premise that God has determined to save everyone and that it’s only their absolutely free will that makes the difference. “Will all people be saved, or will God not get what God wants? Does this magnificent, mighty, marvelous God fail in the end?” (98). He turns to passages that speak of God’s gracious purpose including all nations, not just Israel, to justify his claim that God has chosen to save each and every person. He switches back and forth between an Arminian argument for free will and a Calvinist emphasis on God’s sovereign grace. God always get what God wants, but God wants to save everybody and ultimately some people may choose their own private hell even in heaven.

Bell refers to a church website that says, “‘We get one life to choose heaven or hell, and once we die, that’s it. One or the other, forever.’ God in the end doesn’t get what God wants, it’s declared, because some will turn, repent, and believe, and others won’t” (103). However, that website appears to be paraphrasing Hebrews 9:27: “And just as it is appointed for man to die once, and after that comes judgment, so Christ, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him.” (In fact, the writer to the Hebrews warns in the next chapter—10:27, 31, 39—that those who turn away from Christ of “a fearful expectation of judgment, and a fury of fire that will consume the adversaries…It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God…But we are not of those who shrink back and are destroyed, but of those who have faith and preserve their souls”.)

Back to the Arminian argument: “Although God is powerful and mighty, when it comes to the human heart God has to play by the same rules we do. God has to respect our freedom to choose to the very end, even at the risk of the relationship itself” (103-4). Given what Bell already knows—namely, that love is God one defining attribute, God has chosen to save everyone, but genuine love demands that free will have the last word, it must be that people have a second chance at salvation after they die. I confess that this part confused me at first. Why do people need a second chance for salvation if they aren’t un-saved in the first place? But then the logic becomes clearer: given enough time, even the hardest hearts will open themselves to God’s goodness. So maybe there are “endless opportunities in an endless amount of time for people to say yes to God. As long as it takes, in other words” (106-7). Apparently, the only thing sinners need is more time plus suffering/mercy. Just as subjective as that blurry line between heaven and hell is the line between mercy and judgment. God’s justice is never retributive, but only restorative. Not surprisingly, he calls upon Origen for support (107), as if the ancient theologian had offered a legitimate option in church history. At the center of the Christian tradition since the first church have been a number who insist that history is not tragic, hell is not forever, and love, in the end, wins and all will be reconciled to God…Or, to be more specific, serious, orthodox followers of Jesus have answered these questions in a number of different ways” (109).

However, Origen’s views—especially the eternal pre-existence of the soul, the questioning of the bodily nature of the resurrection, and the restoration of all souls through a series of purgative re-incarnations (apocatastasis) were condemned at the Synod of Constantinople in 543.

Rather than engaging in serious exegesis, Bell simply asserts another deductive dogma: “Restoration brings God glory; eternal torment doesn’t” (108). Everlasting punishment just “isn’t a very good story” (110). “Many have refused to accept the scenario in which somebody is pounding on the door, apologizing, repenting, and asking God to be let in, only to hear God say through the keyhole: ‘Door’s locked. Sorry. If you had been here earlier, I could have done something. But now, it’s too late’” (108). Indeed, many have refused to accepted such a scenario, including Noah’s neighbors, but God did shut the door. And Jesus explicitly draws on this example in his warning of judgment (Mat 24:37-39).

The vivid warnings of escaping the coming wrath that we find in the epistles (Rom 1:8; 2:2-5; 5:9; 9:22-24; 14:10; 2 Cor 5:10; Eph 2:3; 5:6; Col 3:6; 1 Thes 5:1-11; Heb 9:27; 10:27; 2 Pet 2:9; 3:1-13; Jude 1:6, etc.) are simply not addressed in this book.

Not even in the Book of Revelation, where we read of “the wrath of the Lamb” and the last judgment in the most vivid terms, making the holy wars of the old covenant pale in comparison, is there any place for everlasting punishment. Everyone is in heaven. Everyone is at the party, even if some insist on sitting in the corner in defiance, creating their own private hell. Thus, even in the New City we’re free to embrace our own hell if we want. “Let’s pause here and ask the obvious question: How could someone choose another way with a universe of love and joy and peace right in front of them—all of it theirs if they would simply leave behind the old ways and receive the new life of the new city in the new world?” (113-14). Again, the deep depravity of the fallen heart is not appreciated in Bell’s account. He assumes that, given enough time and enough experience of the joys of the party, sooner or later the most resolute unbeliever will join in. For Bell, the fact that the gates are never shut means that there’s always an opportunity for those who choose hell to join in the celebration (114-15).

Part 6 appears here.